A $70 million program will try to develop brain implants able to regulate emotions in the mentally ill.

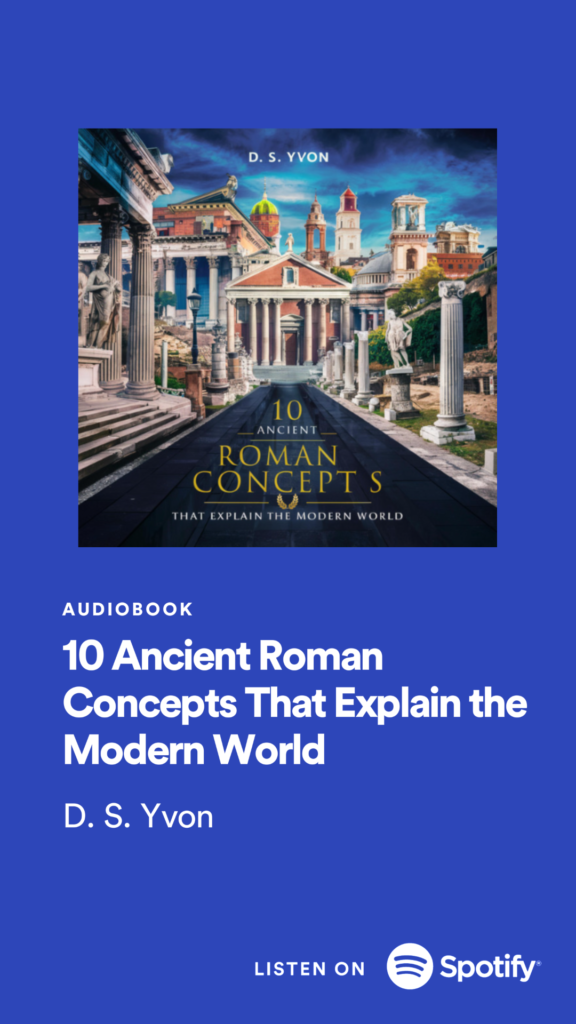

Brain reader: An array of micro-electrodes printed on plastic can record from the brain’s surface. It is 6.5 millimeters on a side.

Researcher Jose Carmena has worked for years training macaque monkeys to move computer cursors and robotic limbs with their minds. He does so by implanting electrodes into their brains to monitor neural activity. Now, as part of a sweeping $70 million program funded by the U.S. military, Carmena has a new goal: to use brain implants to read, and then control, the emotions of mentally ill people.

This week the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, awarded two large contracts to Massachusetts General Hospital and the University of California, San Francisco, to create electrical brain implants capable of treating seven psychiatric conditions, including addiction, depression, and borderline personality disorder.

The project builds on expanding knowledge about how the brain works; the development of microlectronic systems that can fit in the body; and substantial evidence that thoughts and actions can be altered with well-placed electrical impulses to the brain.

“Imagine if I have an addiction to alcohol and I have a craving,” says Carmena, who is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and involved in the UCSF-led project. “We could detect that feeling and then stimulate inside the brain to stop it from happening.”

The U.S. faces an epidemic of mental illness among veterans, including suicide rates three or four times that of the general public. But drugs and talk therapy are of limited use, which is why the military is turning to neurological devices, says Justin Sanchez, manager of the DARPA program, known as Subnets, for Systems-Based Neurotechnology for Emerging Therapies.

“We want to understand the brain networks [in] neuropsychiatric illness, develop technology to measure them, and then do precision signaling to the brain,” says Sanchez. “It’s something completely different and new. These devices don’t yet exist.”

Under the contracts, which are the largest awards so far supporting President Obama’s BRAIN Initiative, the brain-mapping program launched by the White House last year, UCSF will receive as much as $26 million and Mass General up to $30 million. Companies including the medical device giant Medtronic and startup Cortera Neurotechnologies, a spin-out from UC Berkeley’s wireless laboratory, will supply technology for the effort. Initial research will be in animals, but DARPA hopes to reach human tests within two or three years.

The research builds on a small but quickly growing market for devices that work by stimulating nerves, both inside the brain and outside it. More than 110,000 Parkinson’s patients have received deep-brain stimulators built by Medtronic that control body tremors by sending electric pulses into the brain. More recently, doctors have used such stimulators to treat severe cases of obsessive-compulsive disorder (see “Brain Implants Can Reset Misfiring Circuits”). Last November, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration approved NeuroPace, the first implant that both records from the brain and stimulates it (see “Zapping Seizures Away”). It is used to watch for epileptic seizures and then stop them with electrical pulses. Altogether, U.S. doctors bill for about $2.6 billion worth of neural stimulation devices a year, according to industry estimates.

Researchers say they are making rapid improvements in electronics, including small, implantable computers. Under its program, Mass General will work with Draper Laboratories in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to develop new types of stimulators. The UCSF team is being supported by microelectronics and wireless researchers at UC Berkeley, who have created several prototypes of miniaturized brain implants. Michel Maharbiz, a professor in Berkeley’s electrical engineering department, says the Obama brain initiative, and now the DARPA money, has created a “feeding frenzy” around new technology. “It’s a great time to do tech for the brain,” he says.

The new line of research has been dubbed “affective brain-computer interfaces” by some, meaning electronic devices that alter feelings, perhaps under direct control of a patient’s thoughts and wishes. “Basically, we’re trying to build the next generation of psychiatric brain stimulators,” says Alik Widge, a researcher on the Mass General team.

Darin Dougherty, a psychiatrist who directs Mass General’s division of neurotherapeutics, says one aim could be to extinguish fear in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. Fear is generated in the amygdala—a part of the brain involved in emotional memories. But it can be repressed by signals in another region, the ventromedial pre-frontal cortex. “The idea would be to decode a signal in the amygdala showing overactivity, then stimulate elsewhere to [suppress] that fear,” says Dougherty.

Such research isn’t without ominous overtones. In the 1970s, Yale University neuroscientist Jose Delgado showed he could cause people to feel emotions, like relaxation or anxiety, using implants he called “stimoceivers.” But Delgado, also funded by the military, left the U.S. after Congressional hearings in which he was accused of developing “totalitarian” mind-control devices. According to scientists funded by DARPA, the agency has been anxious about how the Subnets program could be perceived, and it has appointed an ethics panel to oversee the research.

Psychiatric implants would in fact control how mentally ill people act, although in many cases indirectly, by changing how they feel. For instance, a stimulator that stops a craving for cocaine would alter an addict’s behavior. “It’s to change what people feel and to change what they do. Those are intimately tied,” says Dougherty.

Dougherty says a brain implant would only be considered for patients truly debilitated by mental illness, and who can’t be helped with drugs and psychotherapy. “This is never going to be a first-line option: ‘Oh, you have PTSD, let’s do surgery,’ ” says Dougherty. “It’s going to be for people who don’t respond to the other treatments.”

DARPA article : http://www.technologyreview.com/news/527561/military-funds-brain-computer-interfaces-to-control-feelings/