How PTSD Was Cured Four Times in 5 Hours

This case study shows how a non-drug intervention can be successfully used to cure PTSD in a Vietnam veteran in under 5 hours.

'Carl, our pseudonymous client, met criteria for at least one Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV) Criterion A traumatic event and a current PTSD diagnosis. In addition, he asserted the presence of one or more flashbacks or nightmares during the preceding month. At the initial assessment, and at 2- and 6-weeks post-treatment, Carl completed assessments for PTSD.'

4 PTSD Memories targeted.

- Rocket Attack, 1971

- Viet Cong Sapper

- Claymore Mine, 1971

- Ditch Rat Bites, 1971

For the full step by step intervention and resources:

Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories-Bourke-Gray-Potts

'Carl, completed semi-structured clinical interviews at baseline to assess their current status and eligibility for participation. The PTSD Checklist-Military version (PCL-M) was administered to all participants at intake, two weeks, six-weeks, 6-months post and one-year post.'

Participants were admitted to the program with a PCL-M ≥ 50. Participants also completed the Posttraumatic Stress Scale-Interview (PSS-I) version at intake (PSS-I > 20) and two-weeks post. Observations of autonomic reactivity were recorded using an in-house instrument, the Behavioral Screening Instrument (BSI), whose results are not reported here. Subjective Units of Distress (SUDs) were elicited during treatment sessions at each elicitation of the trauma narrative using the standard ten-point Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS).

Post treatment assessments relied upon the PSS-I and PCL-M at two-weeks post, the PCL-M and clinical observations at six-week, six-month, and one-year follow-ups. Clinical observations included the cessation of nightmares and flashbacks, the ability to re-tell the trauma narrative with a SUDS rating of 0, a fluid, fully detailed recall of the index trauma, and personal and family reports of positive adjustment.'

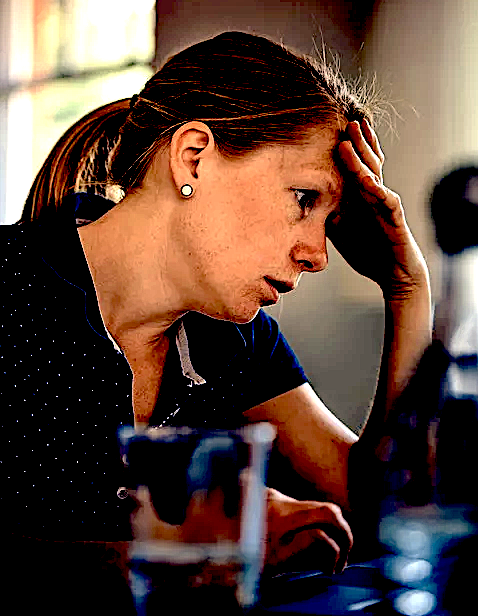

Carl was a talkative, thoughtful, reflective Vietnam vet who reached out for psychological assistance in 1984 for anger and “doing dangerous things that weren’t me”. He was diagnosed with PTSD, major depression, and was prescribed Prozac, which he had been taking for the past 34 years, along with sleep medications. Carl was an experimental subject, which meant that after qualifying to participate in the study he would immediately receive three individualized treatment sessions with the RTM protocol, with no waiting period. Follow-up interviews and measurements happened again at 2 week, 6 week, 6 month and 1 year intervals.'

'Pre-screen. At the Pre-screen, four different trauma events were reported. Carl easily qualified for the study due to three factors. First, Carl showed fast rising autonomic arousal when speaking of each event. Second, Carl was experiencing weekly trauma related nightmares and flashbacks. Third, his pre-treatment scores on the PCL-M and PSS-I were high, scoring 73 (of a possible 85 points) on PCL-M and 42 (of a possible 51 points) on PSSI. He endorsed PTS symptoms in all DSM IV clusters: re-living, avoidant, mood/hyper-vigilance. Based on the 75 minute pre-screen interview one trauma event was identified by the clinician as most physiologically reactive. This agreed with the client’s assessment that this was the most troubling. This event was linked to intrusive thoughts, nightmares and flashbacks 4 times a month.'

Carl reported that the flashbacks happened in the stillness of the night and he would flash back to the sky, red with incoming rockets and mortars. Additionally, he said he ruminated daily on his partner’s death. During a 1 ½ minute re-telling, the client’s hands immediately began trembling and his leg began bouncing up and down. Then, Carl’s voice broke and he physically froze. The clinician promptly interrupted the narrative and he was told, “that’s enough for now.” The topic was changed to the client’s favorite hobby.

The target event took place in Da Nang, 1971.

In a 3 minute timeframe, Carl related the following:

“My worst experience was losing my service dog, Rex. I was part of the canine program at Da Nang and we became very close partners (voice warbles)… We developed a very close relationship. It wasn’t like any of the other units. We worked alone. This particular Christmas morning where Rex was killed (leg and hand trembling, pauses, freezes, head tilted down and right, pauses)… I’ve lived so many years of guilt (posture shifts, voice shifts, head lifts), because I should have died with my dog (voice trembling) … That dog was my partner and I’m alive and that dog died saving my life. When one of the rockets was coming down, Rex could hear the whistling of the fins.

And he lunged, which brought me to the ground. The minute I hit the ground that rocket went off (leg shaking). What I re-live is the Medivac out of the area. I always remember I was laying on the floor of the helicopter and I had a loose leash. I still have (notice shift to present tense) the leash on my hand (voice shaking) and my dog (clinician attempted to interrupt telling, yet client kept talking)… I remember I moved my hand. I never felt it without my dog.” Clinician stood and interrupted saying,

“Thanks, count backwards 5-4-3-2-1, please.” Carl counts backwards. Carl shifted to talk of fishing and the recent purchase of a new rod for fishing. Event was given the name “Rocket Attack, 1971”.

Treatment One began two days later.

1. Rocket Attack, 1971 (8 SUDS)

Treatment 1. Treatment 1 commenced with the first phase of the RTM protocol. Carl learned the visual formats characteristic of the RTM process using practice movies. He chose an activity he experienced recently which was ‘going fishing’ and the bookends (beginning and end points) for the movie were determined. The client was guided through three different versions of the practice movie. Carl was able to see himself dissociated, doing the activity on an imaginary movie screen. Additionally, he was able to take the color out of the movie and watch himself do the activity from beginning to end as a black and white movie.

Associating into the end of the fishing event, in first person, through his own eyes, and going in reverse, backwards through the event, to the beginning, was practiced until it could be executed with ease.

'Client was asked to tune in to the event “Rocket Attack, 1971”. Carl responded by saying it was an “8 SUDs” and “it draws a lot of emotion.” Once the trauma intensity was calibrated, the clinician quickly moved on, changing the client’s focus of attention and physical position in order to ensure a relaxed re-structuring experience for Carl. The clinician directed the client to find a resourceful moment before the event happened, where he was safe. He chose “Ski patrol” at Mt. Green, where he worked stateside immediately before leaving for Vietnam. The end of the event, where he felt that he was safe, the event was over, and he survived, was the “Family gathering”, when he returned home. After doing the set-up from theatre to projection booth, Carl was lead through 11 iterations of the black and white movie watching himself in the theatre as he watched his 21-year-old self go through the rocket attack event. He was specifically directed to stay in the booth and watch the self in the theatre as he watched a black and white movie beginning at the safe image at Mt. Green - a black and white still image of himself on ski patrol. The procedure continued through the rocket attack, the death of Rex, and ended with a still black and white image, Carl, back home at the “Family gathering”.

This movie was run in 45 seconds or less. Carl had little difficulty doing the dissociated black and white movie. Only one time was he observed to associate into the movie, seeing it through his own eyes and in color.'

The variations included: extending the distance of the screen, the speed of the movie, watching only the bottom half and then only the top half, and temporal variations.

The Associated Color Reversal step followed and involved 8 repeated experiences of the event as imaginal, associated, multisensory reversals of the rocket attack ‘undoing itself’ beginning at the end of the event (Family gathering), and in 1-2 seconds moving backwards through the rocket attack to the beginning (Ski patrol). Carl experienced the associated kinesthetics of holding the empty leash and falling to the ground in reverse, undoing themselves. The sound of the incoming rocket was reversed, and events associated with guilt feelings were made a specific element of the undoing experience. After completing these two essential restructuring steps, the client looked visibly relaxed and was directed.

At the end of Round 1, Carl offered the following narrative with added information: “It was Christmas morning. We were advised there would be activity. We were three hours into patrol. Rex heard the high-pitched sound [of the incoming rockets]. He jumped and pulled me to the ground. At the moment the rocket hit the ground Rex was killed. At that point it turned into a Medivac. I now remember I did not leave Rex there alone. Rex was on the helicopter and not left behind. They put him on the helicopter with me. He was off leash. The leash was empty, yet he was there. He was covered in a poncho. I got a letter from the Squadron leader explaining how they had a nice burial for Rex.” When asked by the clinician, “how was this re-telling different?”, Carl responded that “I was comfortable. I did not see myself leaving my dog behind. I did not see the horrific things that I thought I saw. My dog was dead, but my dog was with me. I don’t feel painful. It was a terrible thing, but I understand it. I know what happened. I can’t well up in tears and cry like I normally want to do. I don’t know what is going on or what is happening, but I have a sense of pride in what I am talking about.”

Carl reported the event at a 3 SUDs. Client and clinician then moved on to the revised movies with a better, safer different outcome.

The first version of the revised movie involved Carl acting as a movie director on a movie set with cameras and stunt actors standing in for himself and Rex. In this revised version the rockets overshoot, everyone is down on the ground and OK; the rocket fire stops and they all jump on the helicopter, including Rex, and take off. Then, as Director, Carl yells cut and Carl’s substitute and Rex take off for their dressing rooms. A second revision involved Carl and Rex safely finishing their shift and going to China Beach, so Rex could wash his paws. In a third revised movie, the patrol is finished, Carl and Rex are re-assigned stateside and they fly home.

After running these multiple revised movies several times, Carl is directed to tune into the original event, “Rocket Attack, 1971,” and it is a 2 SUDs. He reflects voluntarily, “I don’t feel that whatever it was… that would take over. I don’t feel I’m leaving him behind. Wow, that’s pretty strong. I feel good, I do. (Here client exhales a deep sigh and takes a Kleenex to dab his eyes. The clinician is calibrating tears of relief.) He’s OK.” Client went on to further comment on the process, “I have no idea what is going on here. I feel in a much better place.”

For Carl, the shift in focus to recognizing that he did not leave the dog behind represented an important pivot point in rewriting the trauma event. Since the event was not yet a 0 SUDS, Carl was instructed to do another round of five black and white dissociated movies and four associated color reversals for the same event. The same bookends are used. When directed to re-tell in detail, Carl related the event in a matter of fact tone. He said the re-telling was different this time in that,

“I’m proud to tell the story. The dog gave his life for me. I’m honored to do that for him. I’m not torn up emotionally. I’m not thinking horrifically bad things. It was war. It is now a 1 SUDS.” Another revised movie was completed with Carl and Rex safely missing the rocket and Rex receiving accolades for his bravery. Revised version was run several times. Carl offered the following comment at this point, “In 40-plus years, I have never been able to discuss something in such a manner, that is, putting it into real perspective. I had to do what I had to do. My dog did what he was trained to do. It was war and we were the casualties of war, but we did the best we could. This is remarkable. This is wonderful.” The event was reported as a 0.

The treatment of “Rocket Attack, 1971” took 78 minutes in total to reach a 0 SUDs rating.

2. Viet Cong Sapper (8 SUDS)

Next the clinician moved on to an earlier Vietnam event, Hand to Hand Combat “Sappers”, that was replicated in a recurring nightmare. A Viet Cong ‘sapper’ was akin to a combat engineer. The task of VC ‘sappers’ was to penetrate American defense perimeters.

At pre-screen, Carl reported experiencing this recurring nightmare at least 4-8 times a month.

The nightmare content was described as follows:

“I am in a battle with no end to it. My dog, Rex, is in the dream and he is aggressively fighting and biting one sapper. I have a knife and am involved in hand to hand combat with a second sapper.”

Carl indicates that he’d wake up in the morning and feel exhausted because it seemed like it never ended. His wife reported that he recently kicked a sliding door off its runner after jumping out of bed during a nightmare. She commented further saying that he frequently talks in his sleep saying repeatedly: “Be careful.”

Carl’s daughter disclosed that many times when she would walk up behind her dad, he would startle, spin around and raise his fists. As treatment one continues, Carl reports the “Viet Cong Sapper” event as follows:

“Rex and I were on night patrol. I went out on patrol anxious every night. Rex and I were always at least one-half mile away from help. It was very lonely on patrol. Drain ditches had outlets around the base. Sappers would come through the ditches giving them access to planes and weapons dumps. I completed 1st quarter of the patrol then started the 2nd quarter where I went down a tunnel. Rex was alerted to action as his ears went up. It happened so quickly. We were there engaged in a fight. Rex took one sapper and lunged at him. I had a rifle but no way to get in position to do damage. The sapper was on me and I pulled my ka-bar [combat knife]. I stabbed him in the stomach and cut the side of his throat (facial muscles tighten, voice quickens, breathing gets shallower). I cut his jugular vein and he was bleeding. He went to the ground and I just kept stabbing and stabbing (throat tightens, voice tone changes). I don’t want him to get up and move. Sappers taped their chests with duct tape so that if they got injured they could keep going and get to their target. They are like terrorists. The most troubling part was blood and things have a terrible odor. I remember the whole picture (looks at the ground) of chaos that I painted. It’s never going to come to an end. That was the first time in my life fighting like that… fighting for my life. It felt in slow motion and ‘please stop, please stop’, I was saying to myself. I did not want to be there at the base of this tunnel with the Viet Cong sapper.”

Client reflects that with that re-telling he felt the emotion in his chest and re-experienced stabbing and stabbing and seeing the guy bleeding from his neck. During that telling the clinician observed shifts in breathing, voice tone and tempo, facial muscles tightening and skin color draining. The client described the event at an 8 SUDS with feelings of fear and terror linked to it.

The client and clinician decided to use the same bookends as used in the event “Rocket Attack, 1971”. The client was then returned to the movie theatre, was seated, then guided to put the first still black and white image on the screen. Next, he was directed to float up to the projection booth leaving his body in the theatre. From the booth he was instructed to watch the self in the theatre as he watched the sapper movie of the younger self. The client was guided through 11 iterations of the black and white sapper movie at a distance and dissociated, with each lasting 15-20 seconds or less. The accelerated speed of the dissociated reviews was designed to counteract the client’s description of the event as perceived ‘in slow motion with no end’. Once the self in the theatre was comfortable watching the event in black and white, Carl was directed to come down from the projection booth, re-enter his body in the theatre, walk down to the screen, and step into the end bookmark, “Family gathering”. Seven iterations of the associated color reversal followed. The client completed all steps successfully.

When directed to re-tell the event in as much detail as possible, Carl described it more briefly indicating that when the sapper came upon him and Rex, he slashed him, fell on top of him and stabbed him several times. From there, a SWAT team came. He points out that there was no equipment in 1971 like they have today. He was out on patrol with no radio turned on. He says that this re-telling was different in that he no longer felt tension in his chest and hands. “I was comfortable with it. I did what I was trained to do. My dog did what he was trained to do. If I did not respond the way I did, I would not be here talking to you. It was war.”

Carl’s pre-treatment narrative, Carl reported that he only stabbed the sapper three times, and no longer described the event as “slow motion over and over again”. The event was rated with a SUDs level of 2. Two different revised movies were created and run with multiple revisions. The first revision involved a movie director version on a movie set with stunt actors and Carl as director. All equipment was fake, non-crippling gear and actors got up from the ground after the fight and went to a staff party. This version was run several times.

The next safer outcome involved Carl and Rex on patrol, sighting the Sappers from a distance, exchanging gunfire, and taking the Sappers out. Carl liked this version, commenting: “There was no rolling around in sewer water. Engaging at a distance is much better.”

He ran this revised version multiple times. The client then re-told the actual event and indicated that his revised perspective was that “It was a night in the jungle. A night doing my job. It had to be done. I feel it’s a 0 SUDs now.” For this trauma, the client’s entire experience took 36 minutes. As the clinician drew the session to a close, the client was asked how he was feeling. His response was: “I’m not sure. Wow. I’ve sat for a couple of hours and I’ve done some things here that I’ve tried to do with others in a different way and never have come close to having this type of ending with a session. I love it. I want to build upon that.”

Treatment 2. Carl returned for RTM session 3 days later. He described his experience over the past few days as follows:

“A lot of processes inside myself have changed. Since the last session my thought process has changed when it comes to Vietnam. I’ve been talking with my wife and daughter. I remember it as a process. I go to Vietnam, did what I had to do, but came home to a good process. I wasn’t stopping off and dwelling (on past events). I wasn’t getting these charged up feelings. I feel more rested and comfortable than I have in a long time. We talk about the process (RTM). It’s absolutely phenomenal. It’s hard to imagine how somebody can be dealing with something like this for so many years and having psychiatric care and getting medication for umpteen years. I’m off the sleep meds and blood pressure pills and I cut back on the Prozac. I want to take this good feeling and expand on it. I’ve been talking with the neighbors and getting out for a morning walk. My front door is not a blockade for me anymore. I go to bed after the late evening news and am sleeping with a clear head. No more checking doors and windows. Before, I know I’d lock the doors and windows and then go back and check them again. I’m calm now.”

0 SUDS. 36 minutes of RTM Treatment.

3. Claymore Wire, 1971

The clinician directed the client’s attention to a third Vietnam traumatic event, “Claymore Wire, 1971.”

At pre-screen, the event was described as follows: “I was assigned at the Da Nang airport to patrol the perimeter. Incoming Rockets were going off. When rockets were going up, there would be infiltration happening somewhere on the base. I was in charge of the machine gun on the vehicle. As we were moving, a claymore wire was set between the trees. (Pause and deep breathe.) The wire wrapped around my neck. (Swallows and color drains from face.) I got pulled out of the turret. Fortunately, the wire broke.” The shift in voice tone and tempo are audible as he expressed with a horrified look on his face: “I would have been decapitated if that wire did not break.”

Because this event was identified at Pre-screen by Carl as significant, and sympathetic arousal was observed, the clinician decided to check and see how he represented the event in the present time. Carl started the description by saying, “It was the 1st event that set a precedent in my mind that this is dangerous. I had only been in country for a week and it was the beginning of events that would weigh on me for years and years and years.” He went on to relate the event with the same details described at Pre-screen, yet was observed to tell it smoothly, with even voice tone and tempo and no autonomic arousal. Client indicated that: “I did not feel choked up and, to be honest, I talked about this with my family since that the last meeting. It’s done. There is no component of it that is troubling.”

4. Ditch Rat Bites, 1971

The Clinician moved on to a 4th Vietnam event, “Ditch, Rat Bites, 1971,” that related to a long term rat phobia.

This traumatic memory is somewhat reminiscent of a scene from First Blood, starring Sylvester Stallone where Rambo walks through muddy water while bitten by rats.

At pre-screen, Carl reported this event with a terse, rapid voice tempo, saying: “Rockets and mortars were incoming. I jumped into a sewage ditch. (Facial muscles tighten, posture shifts.) Rats were biting all over my body and holding onto my skin. (Vocal pitch raises.) I get medevacked to Saigon for rabies shots.” In an interview with client’s adult daughter she reported that when she was younger their family physician wanted her to get a pet. She chose a pet hamster. She said that anytime she brought it in the room, her father would flinch and start sweating.

At the 2nd treatment client and clinician were 25 minutes into the session and Carl’s re-counting of the event sounded as follows: “It was 3 am in the morning. Rex and I were on patrol. Around the base were many sewage ditches. This was how they transported waste. Trenches were a critical point for securing our property. VC sappers would crawl through them. This morning there was rocket, and mortar fire, and they would land close. I literally jumped into the ditch. Within seconds the rats were all over me; it was like a biting frenzy. Rex stayed on the bank. After 15 seconds I jumped out of there. It took 2-3 days before I got help. Rats were noted for their rabies. If you were bit by a rat, you could assume you were rabid. I got back to the base in Da Nang and cleared up the wounds on my hands. I decided to go through a course of injections. I had a terrible reaction to the duck embryo and they medevacked me to Saigon.”

The clinician asked about the most troubling part of the event and the client indicated: “The smell and noise. I smell the sewage (note shift to present tense) and feel them biting (rubs his fingers together).” Clinician calibrated as Carl associated into his worst second in the ditch and re-experienced the smells and sounds. The client then shifted to a dissociated perspective and commented further: “You could not see anything. They were big, black and making a noise. I couldn’t get out of the ditch fast enough. I was confined and did not have control. If I saw a mouse or rat today, I would get pretty tense. (Client looks down and imagines rodent and tightens throat.) I want it removed.”

Carl evaluated: “Telling it now was definitely less intense than before. I go to my happy place, Mt. Green ski patrol.” Carl reported event at a 4 SUDS level. RTM protocol treatment proceeded. RTM process for Carl involved the same bookends, “Mt. Green ski patrol” (beginning) and “Family gathering” (end point). Client returned to the movie theatre, floated to the projection booth, and watched self in theatre watch the younger self go through the event in black and white. Black and white movie variations were repeated 9 times, including lightening the movie to shades of gray due to the night time context of the event. Brightening the movie to shades of gray and running it very quickly so that the self in theatre could see the younger self in the ditch and then jumping out quickly, was reported as comfortable to watch by the self in the theatre. The associated color reversal step was repeated six times. The client was able to do this step handily and each iteration involved undoing a sensory component. The sounds of biting rats were experienced as receding, the smells fading and the felt sensations reversing. Each iteration ended at the start point (Mt. Green, skiing), where the younger self was safe and away from the rats. The narrative followed: “Rex and I were on patrol. There were heavy rockets and mortar. My number 1 instinct was to get down to the ground as low as I could. I jumped into a ditch that was full of rats and sewage. I was bitten numerous times. I finally jumped out of the ditch. I notified the medical folks what happened. It was 1 ½ days before I could get to a place for medical attention. I went to Saigon for 10 weeks of treatment.”

The clinician then asked: “How was that re-telling different this time?”

Carl responded: “It feels like part of a process I went through. I don’t have that horrible, choked up panicky… it’s over. I can think of the memory, yet the good outweighs the bad. I go to my safe place, Mt. Green. This event is just a memory. As I close my eyes this event is back from me.” Client rates event at 1 SUDs. Clinician decides to do some revised movies even though the event is at a suitable SUDs rating. For a revised movie, Carl indicated that he wanted the smells of popcorn and cotton candy wafting through the event, bunny rabbits in the ditch and landing on green grass. This revised movie was run disassociated, then run associated 8 times. Carl then re-told the actual event and said: “It’s a 0 SUDs. It’s like I go from combat to a Disney movie. It’s amazing. I feel no panic.” The clinician tested further and asked him to imagine a rat in his garage at home. He indicates, “I see it. It’s not going to hurt me. I shoo him out.”

Treatment of this event took 30 minutes in total.

Treatment 3. Carl arrived at treatment 3 saying he was sleeping well and had no flashbacks or nightmares related to the treated events. He was asked to re-tell each of the 3 events. With each telling no reactive indices were reported or observed. Carl indicated there were no other events in need of RTM treatment. The clinician and Carl met for 15 minutes and Carl left.

Treatment Outcomes. The two-week follow-up consisted of repeating the PCL-M and PSSI, the client was also directed to re-tell the target trauma. In Carl’s case “Rocket Attack, 1971” was the event specified. Family members, if present, were interviewed. At the 2 week follow-up, Carl’s wife and daughter volunteered their observations as to differences they were noticing post-treatment. For the three other follow-ups (6 week, 6 month and 1 year), only the PCL-M was administered. The Post Treatment Behavioral Assessment (not reported here) was conducted at all three follow-ups, in order to assess flashbacks, nightmares, and maintenance of behavioral changes. The 6 month and 1 year follow-ups were conducted over the phone.

After two weeks Carl met with the psychometrist. At that time, his score on the PCL-M had gone down from 73 (intake) to 17 (2 weeks), a 56-point decrease. None of the DSM IV symptom clusters were endorsed. His score on the PSSI diminished to 0, a 42-point difference. He reported no flashbacks or nightmares in the past 2 weeks. Specifically, the combat nightmare with the sapper, which had been happening 1-2 times weekly, had not returned. Carl went from sleeping 5-6 hours nightly to a full 8 hours sleep. Carl commented that, “It’s amazing to wake up feeling good. Sleep is half the battle. Since night patrol in Vietnam, I’ve been a night person.” No physiological arousal was observed or reported in relation to the narrative.

Carl was clearly reporting absence of re-living/intrusive symptoms, specifically no disturbing image of Rex’s death, feeling upset when reminded of death and killing, or spontaneously having physical reactions like breaking out in sweats when reminded of Vietnam events. His post-treatment behavioral reports further testified to the shift in re-experiencing symptoms. First, he verbalized: “When I look at Rex’s picture on the wall, it’s more of a positive for me.” Second, he offers, “I am not wearing Rex’s dog tags anymore. They are with my other dog tags. I have never gone without them. I took them off after treatment 2. I put that part of Rex I always felt had to be here (pointing to his heart) aside, in another place.”

Changes in avoidant symptoms were marked by significant shifts in Carl’s thinking and behavior. Rather than having to work to push trauma related thoughts and feelings aside, Carl reported, as early as the beginning of treatment two, that he comfortably talked to his wife and daughter about the treated events, Rocket Attack, 1971 and Sappers, as well as the Claymore wire event. The breakthrough for him was that he felt comfortable doing so with no tearing or other sympathetic arousal. Carl indicated he had reconnected with his fishing partner with whom he had not spoken in 8 years. He said that during the call: “There was no loss of words; no feeling of having to explain. It was like we just got out of the boat together. Now I want to socialize and communicate. I feel no need to be back in a suffering position. Before I would do anything not to put myself in a position to socialize. Now there is no discomfort talking to people.” So, rather than avoiding activities and situations, and having no interest in free time activities, Carl was talking with neighbors and engaging with family members rather than detached. His wife and daughter echoed these changes. His ‘zest for life,’ as he described it, contrasted sharply with past thinking that, “I thought tomorrow would bring nothing but pain and anguish.” Rather than no future plans or hopes, Carl described planning ahead: “I try to make every day an active day. I have been walking and gardening. I plan ahead for short fishing jaunts.” Carl was affirming his future and most definitely conveying a future orientation. Carl says of a difficult family situation that arose recently that, “Unlike in the past, I did not feel myself getting dragged down.”

Carl reported handling this situation decisively, without the tangle of emotions he would have in the past. His emotional palette involved a wider range of emotions, and greater clarity in thinking was his report and the clinician’s observation.

Carl displayed and reported a significant reduction in his level of arousal. The client’s wife and daughter were interviewed and echoed this shift in behavior. The wife reported that when she and Carl would watch TV crime or history shows involving loud banging noises, she was observing that he was no longer startling and jumping out of his seat as he had for years. She offered that he is “so much calmer.” Both wife and daughter echoed their pleasure in Carl’s calmer demeanor indicating, “If dad was in a mood and on edge the whole family would be on edge.” The earlier report at treatment two of no longer being obsessed with a house break-in and compulsively checking on doors and windows, further verified Carl’s decreased need to be on guard and super-watchful. Carl summed up the two-week follow-up by saying: “I’m getting off the Prozac. I’ve been taking 60 mg for as long as I can remember. I’m doing a gradual cutback using a Harvard medical process. When we meet for the 6 week follow-up it will be my last day. Now I want to socialize and communicate.” Carl summed up the follow-up by reflecting: “A significant change was made which impacted how I thought of each event. I have lived with this for 40 years and half of that trying to hide the emotion and pain and then to the point where it comes out. Now there’s an opportunity. I am a changed person after 40 plus years.”

At the six week, in-person follow-up (4 weeks later) scores on the PCL-M were recorded at 17, retaining the 56 point decrease seen at the 2 week follow-up. Carl reported no flashbacks or trauma-related nightmares. He reported socializing, exercising, feeling safe, calm and energized. Carl indicated he had just taken his last 10 mg dose of Prozac earlier that day. Carl had been on that medication for 30 years and was glad he no longer had to depend on it to feel good throughout the day.

At the six month follow-up, Carl’s score on the PCL-M remained stable at 17. He reported no flashbacks or nightmares. The six month follow up happened in February. Carl reported enjoying Christmas Eve and Christmas day, and the anniversary of Rex’s death, for the first time in years. This was in marked contrast to the report of his daughter, 4 months earlier, who had indicated that previously, for every Christmas Eve, for as long as she could remember, “Dad would toast Rex and then sit in silence, alone, for hours. On Christmas day he would seem melancholy all day.” Carl also indicated that this Christmas went smoothly. He reported feeling joy and a deep appreciation for life as he talked with family and visitors and his toasts were a celebration. At the one-year follow-up, Carl again scored 17 on the PCL-M. No flashbacks or nightmares. He reported sleeping comfortably, enjoying his wife and family, socializing, walking, and continuing to experience a “zest for life”.

Once the central trauma (Rocket Attack, 1971) and an important second trauma (Sappers) had been successfully treated, the process streamlined in a significant manner and its effects generalized to other events that might previously have needed treatment, or more treatment.

Streamlining was apparent in the lessened temporal investment in the treatment of later traumas. The first event took 70 minutes, the second and third took about half of that (36 and 30 minutes, respectively). This suggests that practice effects after the first treatment were a significant contributor to later treatments. Not only had the basic cognitive elements been practiced multiple times before (practice sessions) and during treatment (11 or more black and white movies and multiple associated reversals and rescriptings), but their subsequent negative reinforcement through the lessening of negative affects (fear, anxiety, sympathetic arousal, loss of control) may be presumed to have increased their availability and utility (behavioral salience) across treatments and sessions.

We may also suspect that the new behaviors, through the same mechanism of reconsolidation that we use as a major explanatory element, became incorporated in the meta-experience of the class of negative and intruding psychological states. So that now, when he thinks of rats, the phobic response is gone, and they are imagined, spontaneously, as bunnies. This process may be related to Gregory Bateson’s (1972) concept of second level learning (Learning II), in which the organism learns how to learn and learns to apply the learned behavior in similar contexts (Bateson, 1972; Kaiser, 2016; Tosey, Visser, &Saunders, 2012).

It is interesting to note that Carl so embraced what he called his ‘happy place’ that the bookends at the beginning and end of the “Rocket Attack, 1971” were used as bookends for the second (Sappers) and third (Rats in the Ditch) treated events. This suggests that these were effective for him in delimiting the traumatic space. That is, they really were safe places in which the trauma had either not yet happened or was truly over as an existential reality. Moreover, they, or their feeling tones, appear to have been integrated into his perception of the traumatic memories.

At one point, Carl refers to accessing the Mt. Green ski patrol scene as his happy place. The bookends apparently provide emotional contexts that he now, consciously or unconsciously, uses to reframe the meaning of potentially traumatic events. This may reflect that these “bookends” were in fact incorporated in the larger context of the fear memories as suggested below:

In previous reports (Gray & Bourke, 2015; Gray & Teall, 2016; Gray, Budden-Potts, & Bourke, 2017; Tylee et al., 2017), we have emphasized our belief and intent that the rescripting exercise in the second part of the intervention does not change the original memory, but provides a weakening of its salience and its meaning as an enduring threat in the present time. Here we note that Carl’s restructuring of the rat attack as a Disneyesque fantasy of soft grass, the odor of popcorn, and fuzzy bunnies may have been carried forward into everyday life as an alternate interpretive context for responding to rodents in his every-day life. In an imaginal test following the revised movie we noted above:

Carl wanted the smells of popcorn and cotton candy wafting through the event, bunny rabbits in the ditch and landing on green grass. This revised movie was run disassociated then associated 8 times.

Carl then re-told the actual event and said:

“It’s a 0 SUDs. It’s like I go from combat to a Disney movie. It’s amazing. I feel no panic.”

Clinician tests further and asks him to imagine a rat in his garage at home.

He indicates: “I see it. It’s not going to hurt me. I shoo him out.”

Here we see an imaginal, metaphorical extension (Skinner, 1957) of the revised event to similar contexts. This also reflects our discussion of Batesonian Level II learning (Bateson, 1972), above.

We note that there were several traumas that either were mentioned in intake or arose only after treatment of the other traumas, that Carl felt no longer needed treatment. He felt that they had become just part of his process. Specifically, his near decapitation by the tripwire of a booby trap connected to a claymore mine, was regarded as no longer traumatizing.

Generalization of the behaviors learned in the context of the treatment also appears in his interpersonal relations, his self control, and a general loss of hypervigilance. This supports our previous claims that insofar as other personal issues and comorbidities are directly related to the index trauma(s), they will often be resolved (Gray & Bourke, 2015; Gray & Teall, 2016; Gray et al., 2017; Gray & Liotta, 2012; Tylee et al., 2017). So, Christmas is redeemed, obsessive checking of home security disappears, self-control is manifested in difficult interpersonal relations, etc.

We again point to the persistence of Carl’s positive adjustment at one year post. At the one-year follow-up, Carl’s PCL-M remained stable at 17. He reported neither flashbacks nor nightmares. He was sleeping comfortably through the night, enjoying his wife and family, socializing, walking, and continuing to experience a “zest for life”.

Observations

At the beginning of treatment, Carl, like all clients in the study, met diagnostic criteria for current PTSD using PCL-M. The PSS-I was also captured at intake and two-weeks post. Carl scored far above the intake criterion of 20. His two week score was 0. Carl’s SUDs ratings began at 8 for the most intense trauma and decreased to 0 for all traumas at the end of treatment.

When trauma narratives were elicited at follow-up sessions, SUDS levels remained at 0.

At baseline, Carl had shown clear signs of autonomic reactivity, including tearing, freezing, color changes, breathing changes, loss of detail and the inability to coherently relate the entire narrative. At follow-up, his capacity to recall the events fully, as coherent narratives, without the observable indicia of autonomic arousal (tears, flushing, pausing, freezing, changing color and vocal tone, etc.) attested to his changed comfort level with the material. He also indicated that they were now comfortable with the trauma memories and that they were viewed as distant, relatively dissociated memories.

Several significant observations may be made regarding RTM, PTSD and the nature of the observed changes:

a) Here (and in the larger study), the client spontaneously reassessed and reintegrated the trauma memory into a fuller, more self-affirming vision of their own past. This suggests that, rather than being the path to recovery as hypothesized by some (Brewin, Dalgleish, & Joseph, 1996; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2006), these changes may be the fruit of the transformed perceptions created by the RTM process.

b) With Carl, as with all of the treatment completers, reduction of the felt impact of the trauma, as evidenced by reduction in SUDs, was associated with more complete memory retrieval, more coherent narratives and a larger perspective on the event itself. Moreover, as the negative affect surrounding the index trauma decreased, this suggests that the narration is less the curative agent, as expected in CPT (Brewin, Dalgleish, & Joseph, 1996; Resick, Monson, & Chard, 2006), as it is evidence of trauma resolution. This is supported by a growing body of evidence to the effect that stress and strong emotion impair various memory functions (Diamond, Campbell, Park, Halonen, & Zoladz, 2007; Samuelson, 2011).

c) For Carl and other cases in the study, comorbid diagnoses including depression and guilt were eliminated or at least ameliorated with the resolution of the intrusive symptoms. This has been reported in other studies of RTM (Gray & Bourke, 2015; Gray & Liotta, 2012; Tylee, et al.2016) and have included the cessation of substance abuse/dependence and marital discord. The same effect has been observed by Resick, Monson and Chard with CPT (2006). This suggests that, in some cases, co-morbidities are maintained as responses to the intrusive symptoms of PTSD and not as self-maintaining syndromes.

d) Despite the listing of the age of the memory as a boundary condition of the reconsolidation phenomenon, such that older memories tend to resist labilization (Agren, 2014; Fernández, Bavassi, Forcato, & Pedreira, 2016; Forcato, 2007; Kindt et al., 2009; Lee, 2009; Schiller & Phelps, 2011; Schiller et al., 2013), these results, treating traumas with a life span of 46 years, suggest that some other interpretation is needed. We lead to the belief, with Lee, Nader, and Schiller (2017), that the replay of traumatic memories as flashbacks and nightmares maintains them as current memories. That is, each time the memory is evoked and labilized through the expression of intrusive symptoms, it is reconsolidated as a present-time threat, making it more susceptible to labilization and reconsolidation than older memories not renewed in this manner.

Summary

The client presented in this case study illustrated successful PTSD treatment using a novel, brief intervention requiring fewer than 5 hours of treatment. Using diagnostic criteria for Military trauma (PCL-M ≥ 50) his intake score was 73 and no longer met criteria for PTSD diagnosis following RTM. These gains were maintained, as reported above, at one-year posttreatment. These results are noteworthy in that Carl suffered from multiple, treatment resistant traumas, a complex trauma history, and had suffered from PTSD, for 46 years. Carl had previously been treated to little or no avail by the Veterans Administration and various veteran outreach agencies.

These results support RTM’s presentation as a brief, effective treatment for PTSD in those cases whose symptoms focus upon intense, automatic, phobic-type responses to intrusive symptoms.

To learn more about the clinical use of memory reconsolidation, this PDF by Bruce Ecker is over 90 pages and a good start. https://www.coherencetherapy.org/files/Ecker_2018_Clinical_Translation_of_Memory_Reconsolidation_Research.pdf

The study for this article is from the RTM-Bourke-Gray-Potts study.

Learn the mental training strategies used by the military to clear veterans of PTSD. This is the strategy mentioned in the Washington Post that is considered the most effective and least known protocol for changing problem memories.

Learn the mental training strategies used by the military to clear veterans of PTSD. This is the strategy mentioned in the Washington Post that is considered the most effective and least known protocol for changing problem memories.

Get Over a Breakup and Learn to Change problem memories so you can move forward without the baggage of a past relationship.

Learn how to get over a breakup fast and change the memories of your ex, for good!